From Letters to Sentences: Teaching Young Writers to Build Confidence and Skill

Writing is one of the most critical literacy skills students develop in early elementary, but making the transition from forming letters to writing full sentences can feel overwhelming. If you’ve ever wondered how to teach sentence writing in a structured and effective way, this post is for you!

Many young writers struggle to move beyond copying words or forming incomplete thoughts. Without explicit writing instruction, they may find it difficult to construct complete sentences that clearly express their ideas.

This post will walk you through a step-by-step approach to teaching writing progression—from word-building to constructing meaningful sentences. These practical strategies, combined with structured resources, will help your students become confident and capable writers. The first step to word and sentence construction is letter formation. You can read more about it here.

Why Writing Must Be Explicitly Taught

Writing isn’t something children just “pick up.” They need systematic instruction that builds from foundational skills to higher-level writing tasks.

There are two essential components students must master before they can successfully write sentences:

Letter Formation & Sound Knowledge – Students need to know how to form letters fluently and automatically.

Phonemic Awareness & Sound-to-Letter Mapping – Students must be able to hear individual sounds in words and connect them to the correct letters.

Knowing how to form letters is not enough. Students need direct instruction on connecting sounds to letters and then using those letters to write words and sentences.

Oral Language: The Foundation of Writing

Writing isn’t just about recognizing and manipulating sounds—it’s about understanding how language works. Students need to grasp how sounds come together to form words, how words connect to build sentences, and how sentences work together to create meaning.

Before students can write, they need to talk. Oral language is the foundation of writing. When children share their ideas out loud, they begin organizing their thoughts, structuring sentences, and developing an awareness of how language flows.

If a child can’t segment the sounds in sat, they won’t be able to write it. Writing is the ability to write words and understand how those words function within a sentence. That’s why talking about writing before putting pencil to paper is essential.

Encouraging students to verbalize their ideas, tell stories, and describe experiences helps them build the language skills they’ll need for writing. The more students talk, the more prepared they’ll be to put their thoughts into words on the page. By fostering strong oral language habits, we create a solid foundation for confident, capable writers. Two of my favorite ways to do this are:

Would You Rather Cards – These engaging prompts get students talking by asking them to choose between two options and explain their reasoning.

For example:

Would you rather be able to fly or be invisible? Why?

Would you rather have a pet dinosaur or a pet robot?

By discussing their answers aloud, students practice forming complete thoughts and supporting their ideas, which translates directly to stronger sentence writing.

Look, Think, Talk, Write – This structured approach helps students develop writing ideas step by step:

Look at an image or object and observe details.

Think about what’s happening or what it reminds them of.

Talk about their observations and ideas with a partner or group.

Write down their thoughts in a complete sentence or short response.

This method reinforces oral language, sentence structure, and idea development before students begin writing independently.

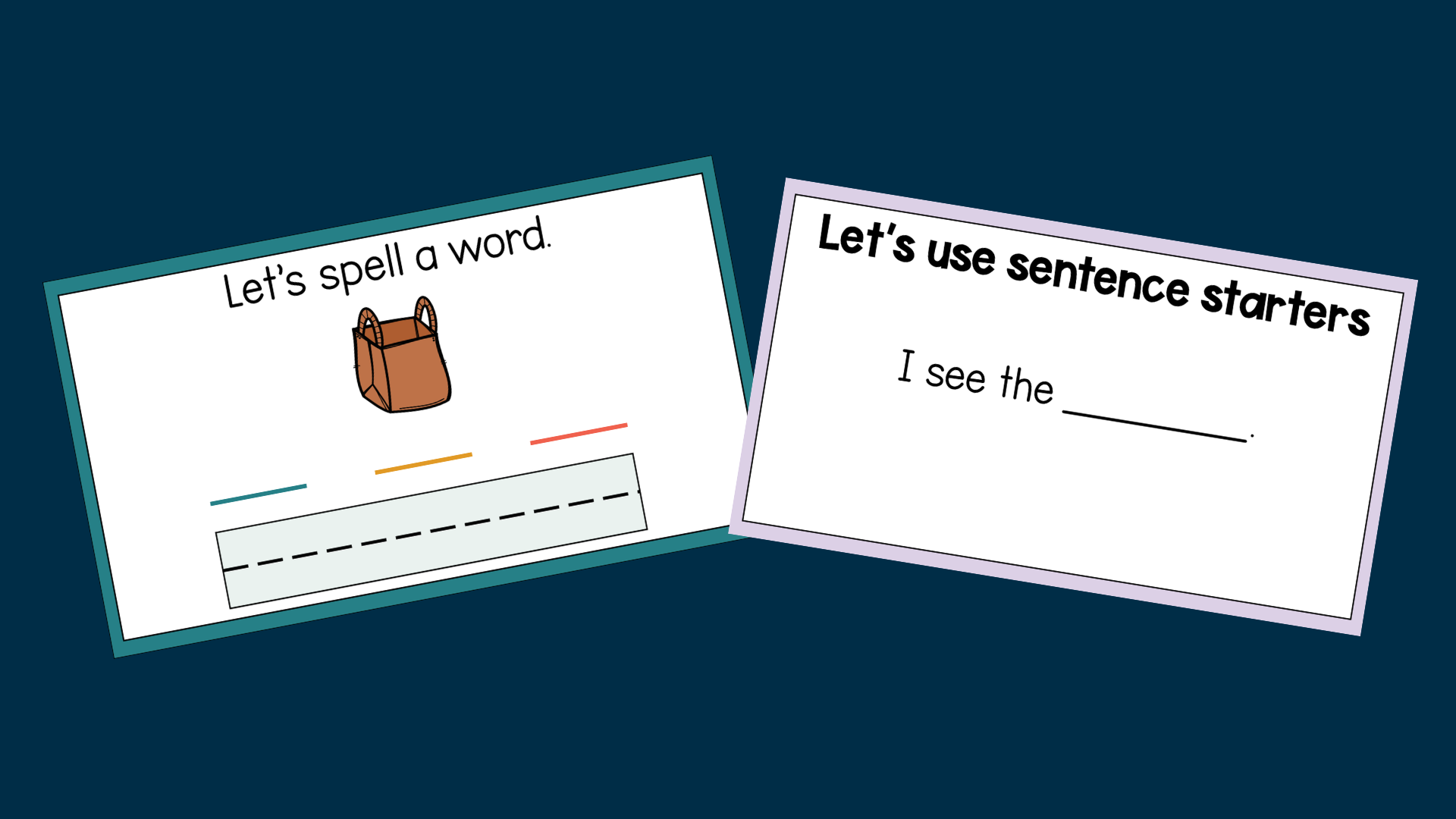

Mapping Words and Building Sentences

Once students can orally segment sounds, we transition them to writing. This step bridges phonemic awareness with written language, helping students connect the sounds they hear to the letters they write.

One way I love incorporating oral language into writing is by having students say, map, and write a word, then use a sentence stem to place that word in a sentence. This structured approach helps students connect phonics skills to meaningful writing while gradually building sentence fluency.

I keep the words connected to the phonics skill they are learning, ensuring that students are working with words they can successfully decode and spell. Once they’ve written the word, I provide a simple sentence stem to help them use it in context. For example, if students are practicing short a words and write bat, they might complete the sentence stem:

I see a ___. → I see a bat.

The ___ is big. → The bat is big.

This method not only reinforces phonics skills but also supports sentence structure, word recognition, and comprehension. By keeping the process predictable and scaffolded, students gain confidence in applying their phonics knowledge to writing full, meaningful sentences.

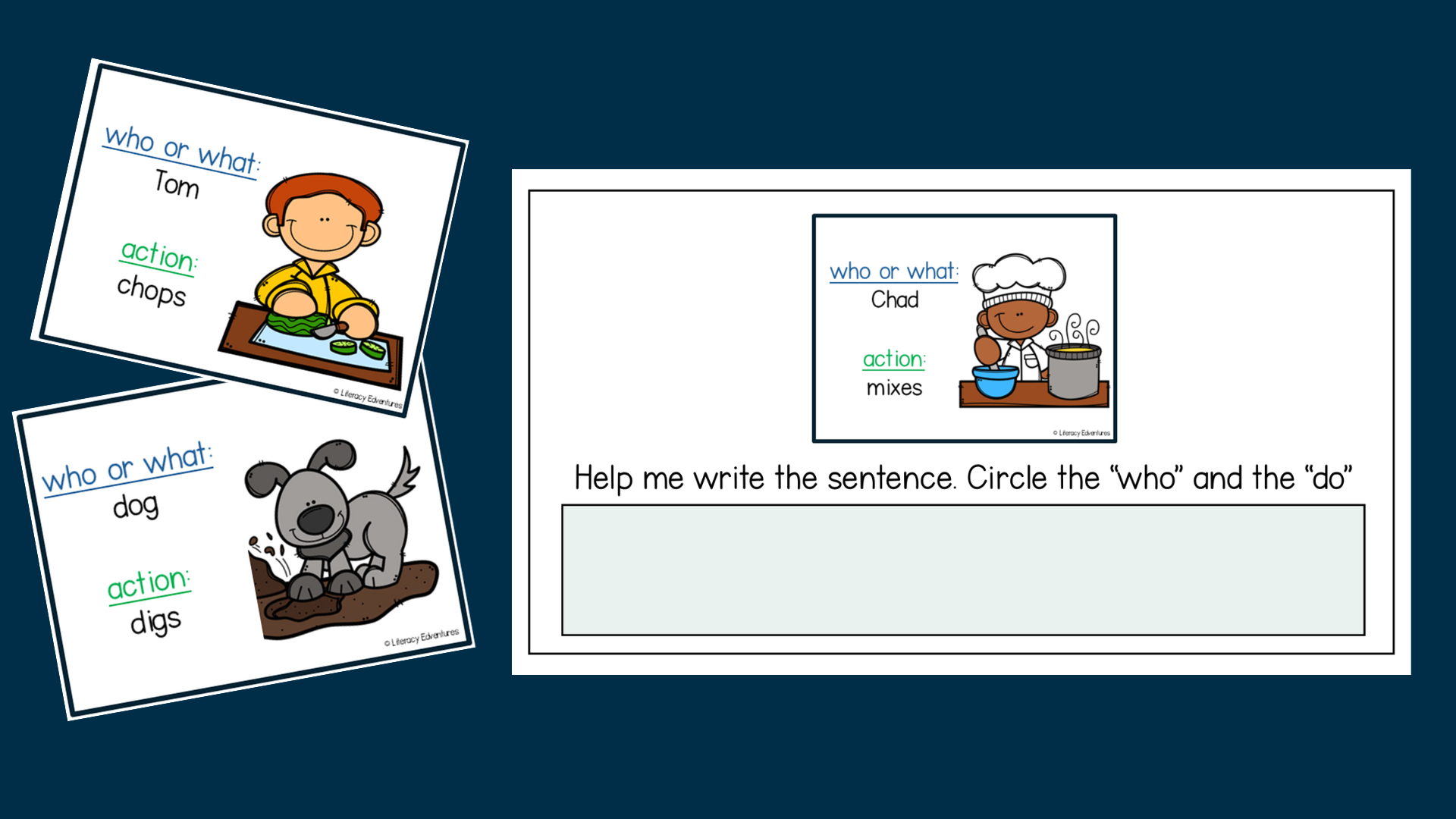

Moving from Words to Sentences

Writing sentences is a huge leap from writing individual words. Before students can construct sentences, they need a solid grasp of sentence structure—what makes a complete sentence and how different parts work together to convey meaning. I love using interactive activities that help students build a strong foundation in sentence writing before they ever put pencil to paper.

Why Understanding Subject and Predicate Is Essential for Sentence Writing

Writing sentences is a huge leap from writing individual words. To construct sentences, students need a solid grasp of sentence structure—what makes a complete sentence and how its parts work together to convey meaning.

At its core, every sentence must have two key components:

The subject – Who or what the sentence is about.

The predicate – What the subject is doing.

Without both, a sentence is incomplete. For example:

✅ The dog ran. (The dog is the subject; ran is the predicate.)

❌ The dog. (Missing predicate—what did the dog do?)

❌ Ran quickly. (Missing subject—who ran?)

Understanding subjects and predicates helps students:

Write complete sentences instead of fragments.

Organize their thoughts clearly, improving readability.

Recognize when a sentence is incomplete or doesn’t make sense.

Develop stronger sentence fluency, reducing run-ons and awkward phrasing.

Once students master this concept, they can expand their sentences by adding details, adjectives, adverbs, and conjunctions. A strong understanding of subject and predicate is the foundation for confident, effective writing.

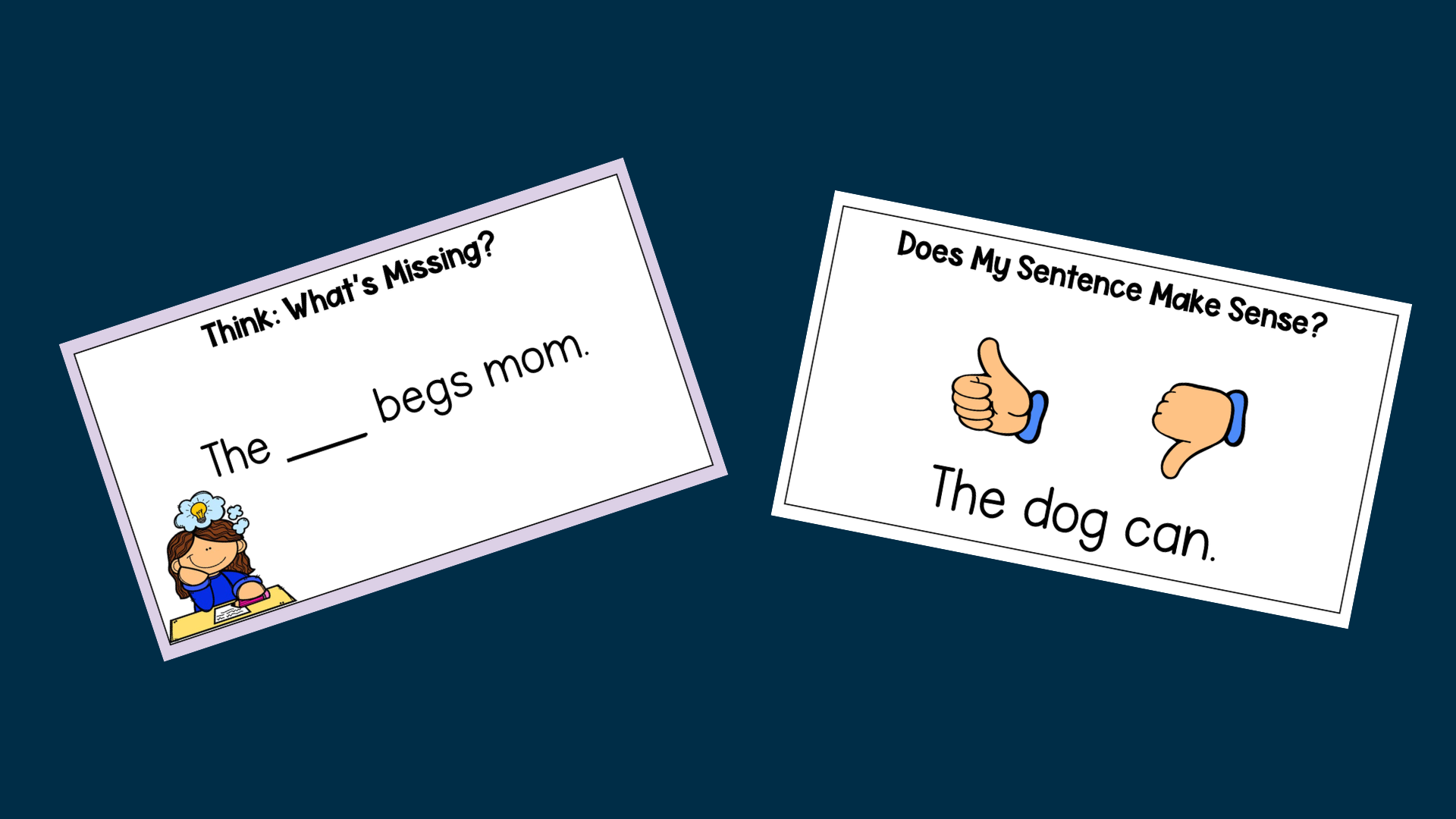

Sentence vs. Fragment: Recognizing Incomplete Sentences

Before students begin writing, they need to recognize the difference between a complete sentence and a fragment. A sentence expresses a complete thought, while a fragment leaves the reader with unanswered questions.

A simple way to check for completeness is the "Does it Make Sense?" test:

Read the sentence aloud—if it sounds unfinished, it’s likely a fragment.

Ask two questions: Who? and What happened? If both can’t be answered, the sentence is incomplete.

For example:

❌ Jumped over the fence. (Who jumped?)

❌ The girl. (What did she do?)

✅ The girl jumped over the fence. (Who? The girl. What happened? She jumped.)

Recognizing fragments helps students self-correct their writing, ensuring their sentences are clear, complete, and meaningful. This awareness lays the groundwork for stronger sentence construction and improved overall writing fluency.

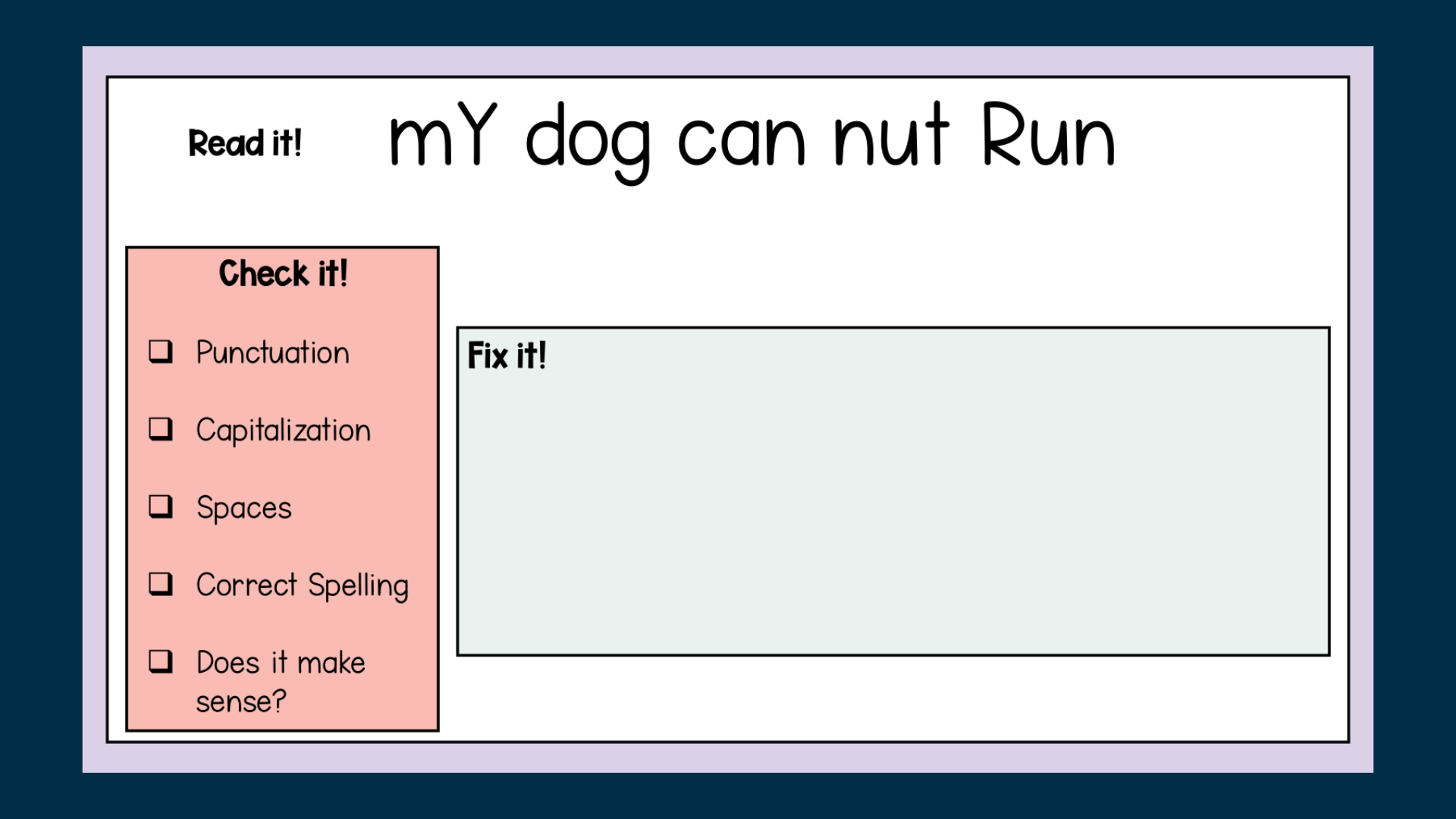

Essential Writing Conventions for Sentences

Once students understand what makes a complete sentence, they need to learn how to properly format their writing. Early writers often struggle with spacing, punctuation, and capitalization, which are key to making sentences readable and clear.

Here are three essential writing conventions students need to master:

Spacing Between Words – Many young writers write sentences as one long string (e.g., thedogranfast). Teaching finger spacing helps them separate words and improve readability.

Punctuation – Every sentence must have proper punctuation to indicate its purpose:

A period (.) signals the end of a statement.

A question mark (?) is used when asking a question.

An exclamation mark (!) shows excitement or urgency.

Capitalization – Every sentence begins with an uppercase letter, and proper nouns (names, places, and titles) must also be capitalized.

These conventions help students move from simple sentence formation to clear, polished writing, setting the foundation for more advanced writing skills.

Dictation: A Powerful Bridge Between Words and Sentences

One of the best ways to help students transition from writing individual words to constructing full sentences is dictation. This structured practice supports early writers by reinforcing phonics, spelling, and sentence structure—all while building writing fluency.

Why Dictation Works

Dictation is a highly effective tool because it:

Encourages listening and writing skills – Students must listen carefully, segment sounds, and write them correctly.

Reinforces phonics and spelling – They apply their phonics knowledge as they encode words into writing.

Builds fluency in sentence construction – Repeated practice with full sentences increases confidence and automaticity.

How to Use Dictation Effectively

To scaffold the process, dictation should follow a progression:

Start with word dictation – Say a word, have students segment the sounds, and write it.

Move to short phrases – Dictate a two- or three-word phrase for students to write.

Transition to full sentences – Say a complete sentence, have students repeat it orally, then write it.

Have students check their writing – Encourage them to read it aloud to ensure it makes sense and includes proper punctuation and spacing.

Dictation helps students internalize sentence structure, improve accuracy, and apply phonics skills in a meaningful way. It’s one of the most effective strategies for bridging the gap between simple word writing and independent sentence construction.

For a deeper dive into how to use dictation in your classroom, check out my blog post: How to Use Dictation to Support Early Writers.

Final Thoughts: The Path to Confident Writers

Teaching sentence writing requires a structured, explicit approach that moves students from oral language to independent writing. By focusing on phonemic awareness, sentence structure, and essential writing conventions, we ensure students develop the skills needed to write with clarity and confidence.

Strong writing starts with oral language, helping students organize their thoughts before putting them on paper. Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, word-building strategies, and sentence structure builds a solid foundation for writing. Scaffolded practice, including oral sentence-building, dictation, and structured activities, supports the transition from words to full sentences. Making writing meaningful and connected to real-life experiences keeps students engaged and reinforces the purpose of writing.

By following this step-by-step progression, students gain the confidence and skills to write independently.

Ready to take the next step? Grab my free writing resource to support your students in mastering the writing process!